Soup as a privilege

The dining hall is a place of both hope and despair. A bowl of hot water—sometimes with a shred of cabbage—can mean the difference between survival and collapse. A typical daily ration consists of a few slices of black bread and balanda—a thin soup occasionally containing a fish head, a potato peel, or a drop of fat. It never provides enough energy. Rations are based on work performance—those who don’t meet the quota get almost nothing.

Chaos, shouting, and tension dominate the food line. Some prisoners fight for scraps; most simply stand in silence. The weakest—the goners—scavenge from the garbage piles, toothless, their limbs swollen from scurvy. Every leftover is worth a life.

Stealing bread is considered a crime worse than betrayal.

“Food is not just a need—it’s everything.”

Scene Objectives

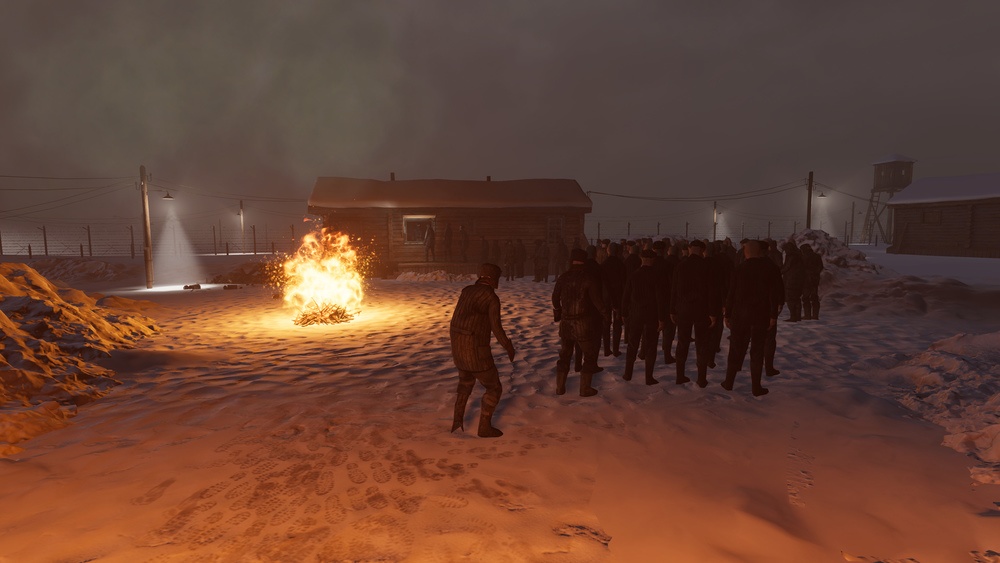

- The player queues for food along with the other inmates. They observe the exhausted crowd, the garbage heap with dochodjaks, and the guards.

- The player is drawn by light and sound toward a disturbance in the distance. Upon approaching, they witness a fellow prisoner being beaten to death by others for allegedly stealing bread.

- The attackers flee. The blame falls on the player, who is sent to solitary confinement.

Message

The scene presents food as the central axis of camp life—a means of survival, conflict, and distorted relationships. It confronts the player with the collapse of dignity and solidarity in the face of hunger. It shows a social hierarchy shaped by physical exhaustion and desperation. The order of the food line determines what one receives—those at the back get only hot water. Players witness a range of inmate behavior—some fight, but most stand in apathy, staring into space. The scene also depicts violence as a collective outlet—rage is often directed at the weakest.

In our story, a young inmate is beaten to death for allegedly stealing a piece of bread. The player, as a witness, is falsely blamed and sent to solitary. Speaking out would mean becoming the next victim. Everyone looks away—shared fear and collective guilt send an innocent person into isolation. Prisoners often enforced their own “justice”—or rather, retribution—to protect a fragile order. Stealing food was seen as a crime punishable by death, and this belief was widely accepted.

Historical Context

The daily ration consisted of 500g of bread and a thin soup with a few bits of potato—sometimes just hot water. Such nutrition, especially in the cold, led to malnutrition, disease, and death. The psychological toll was immense. Physical decline brought scurvy, tooth loss, swollen limbs, and slurred speech. The goners—lifeless, dazed, “living dead”—were seen as subhuman. They were often bullied and robbed—no pity, from anyone.

Food became the main tool of control. Any mistake could result in reduced rations. If the quota wasn’t met, the whole group suffered.

Quotas weren’t fixed—they changed depending on the commander’s mood or ambition.

Being placed in a group that failed to meet the quota was an informal death sentence.

For Educators – Discussion Questions

- What was the composition of a typical meal? How did most prisoners behave during distribution?

- What does the camp’s attitude toward food reveal about its social structure?

- Under what circumstances might you be willing to deprive someone of food?

- Why did the inmates punish one of their own so brutally?

- What role does the silence of others play in this scene?